By Adolfo TM

Audio Transcript of this Post:

Toward the end of the Era of the Apostles, near the close of the first century, Clement of Rome, who knew the apostles of Jesus personally, wrote this amazing story when he was an early church bishop to the troubled church in Corinth:

“There is a bird, which is named the phoenix. This, being the only one of its kind, lives for 500 years; and when it has now reached the time that it should die, it makes for itself a coffin … and so dies.

“But, as its flesh rots, a certain worm is engendered, which is nurtured from the moisture of the dead creature, and puts forth wings. Then, when it is grown lusty, it takes up that coffin which contain the bones of its parent and, carrying them, journeys from the country of Arabia even to Egypt, to the place called the City of the Sun; and in the daytime in the sight of all, flying to the altar of the Sun, it lays them thereupon; and this done, it sets forth to return.

“So the priests examine the registers of the times, and they find that it has come when the five hundredth year is completed.”

Clement used this very well-known story of his day to make the resurrection of Christ relatable to his audience:

“Do we then think it to be a great and marvelous thing,

if the Creator of the universe shall bring about the resurrection of them who have served Him with holiness in the assurance of a good faith,

seeing that He shows to us even by a bird the magnificence of His promise?”

Modern-day translation:”Should we really think it’s such a great and unbelievable thing that the Creator of the universe will raise to life those who have served Him faithfully and with sincere hearts—especially when He even uses a bird to show us how amazing His promise is?”

The trouble is, Clement wrote this story as if it were true. Nowhere does he discredit the fable about the Phoenix as a myth of the pagans. He accepts it, according to this one writing. He even adopts it as part of his argument addressing a bigger issue regarding conflict in the church.

To be sure, the Phoenix story appears nowhere in the Bible; however, you can read about the bird in the First Epistle of Clement here. The Greek historian Herodotus (the “father of history”) wrote that he had heard about this bird from the Egyptians, but that he’d never personally seen one. But Herodotus didn’t call it a fable and discredit it, either. (Other ancient records also mention the Phoenix).

For their part, the Egyptians’ side of this story couldn’t be proven until more than 2,000 years after Herodotus made his claim. That’s because it wasn’t until 1881 that an Egyptian source was discovered that substantiated Herodotus’ claim about the local legend. Underneath an Egyptian pyramid (relax “Ancient Aliens” devotees)–was graffiti on the walls. Actually, it was hieroglyphic text which described a bird, the Bennu, who historians say was likely an earlier version of the phoenix as they shared similar properties such as self-creation and divine origins. I won’t get into the Egyptian gods that came into play here, as it can get rather academic; instead, I want to suggest a possible theory on where the Egyptians might have gotten their bird narrative.

With humanity’s origins in the Garden, people spread out over the earth with varying recollections of the past, modifying the historical facts of creation and God with their own twists and takes. Scholars like the late Dr. Michael Heiser have discussed this phenomenon in terms of the “collective memory” of people who all shared the same experience in Great Antiquity. The people would all write about it and have a version of those events, he noted. This view is more likely to be the case than the out-of-date view that suggests the Biblical writers simply copied earlier versions of famous bible stories from their neighbors (see Heiser’s explanation on that, here).

Ok, fine. That still doesn’t get us past the problem of why would a bishop from the first century– who tradition suggests knew the apostle Peter or Paul (Phillipians 4:3)–believe in something no one in or out of today’s scientific community would propagate? I mean, if Clement’s not faithful in the little things, how can we trust him in the big things?

Ouch.

In reality, here’s why it’s not that simple in this case. There’s a tendency in studying history to project the present into the past rather than leaving the past in its proper historical context and trying to understand it within that context (and not ours). Clement wasn’t knowingly creating myth, or modifying an existing story he borrowed from the pagans, or retelling a story he knew was scientifically false; rather, it’s far more likely –if he keep him in his historical context — that he was only sharing what was widely regarded as credible and reliable natural science in the first century to make a larger point about the gospel. The degree to which the Phoenix story seems strange and bizarre to us is the degree to which we’re familiar with a lot of non-scientific stories of past (or present) cultures.

“Wait,” you may protest! “You must be trying to defend him because he was an early church father.” If you believe that, then think of it this way:

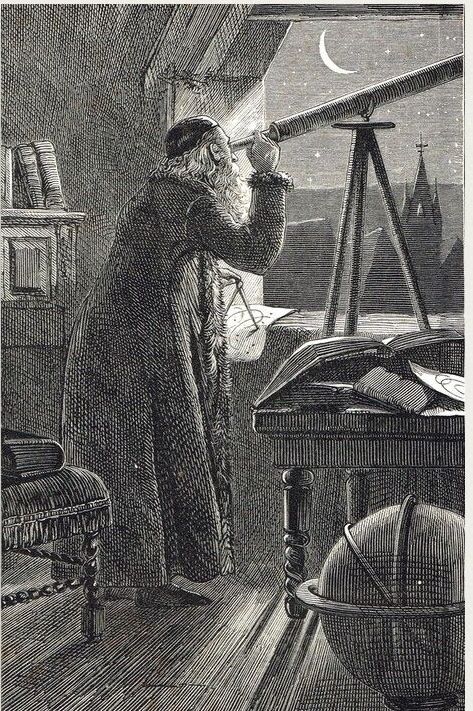

Many people today seem to forget that when Copernicus peered through his telescope and pronounced that the earth was not the center of the universe, he was directly contradicting the accepted, established science of the day. The scientific community was on the church’s side and both were initially against the Polish astronomer. What’s my point? You can easily picture churchmen writing in Copernicus’ day about Jesus’ death and resurrection and noting–at the same time–something like, “As the earth is the center of the universe, so ought Jesus to be the center of our lives.” Except today we know better: the earth is not the center of the universe. (In fact, Earth is the biological center of the universe. And Jesus should still be the center of our lives, ehem).

We learn more about the physical world each day such that the “science” of today becomes falsifiable (non-scientific) tomorrow. Ponder that!

But Jesus Christ “is the same yesterday, today and forever.” (Hebrews 13:8)

One last thought on which I’ll end: Clement’s writings are not part of the Bible, the Word of God. That’s a very important distinction.

The Introduction to the Apostolic Fathers book I’m reading published in the 1800s, noted this, which is something to keep in mind when you read the Church Fathers):

“Their very mistakes enable us to attach a higher value to the superiority of the inspired writers. They were not wiser than the naturalists of their day who taught them the history of the Phœnix and other fables; but nothing of this sort is found in Scripture.

“The Fathers [or their writings] are inferior in kind as well as in degree [in comparison to Scripture]; yet their words are lingering echoes of those whose words were spoken ‘as the Spirit gave them utterance.’ They are monuments of the power of the Gospel.”

“As we read the Apostolic Fathers, we comprehend, in short, the meaning of St. Paul when he said prophetically, what men were slow to believe, ‘The foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men … But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty; and base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are.’ (December 1884).

Amen.

Tomorrow: To reduce Clement to this commentary about the phoenix would be akin to the Corinthians focusing on issues that were non-essential, which is an argument Clement makes in this letter to them. So tomorrow, Lord willing, let’s take a deep dive, a more balanced view of the letter itself, and a more complete picture of this First Century Christian will emerge.

Leave a comment